Canada independence… in pharmaceuticals

- Salle de presse

04/28/2020

- UdeMNouvelles

The head of UdeM’s chemistry department thinks this nation can produce enough of its own prescription medications and not have to rely on imports in the fight against COVID-19.

Canada could be independent in its supply of pharmaceuticals to fight COVID-19 and other diseases if they were entirely produced here, rather than relying on active ingredients to be imported, according to one of the country’s leading chemists.

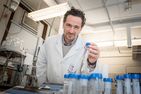

"We have state-of-the-art technology and expertise here to produce just about any small molecule on demand, which can then be sent to drug companies capable of formulating it for the market," said André Charette, head of Université de Montréal’s chemistry department.

On April 18, Quebec Premier François Legault said the province that may soon face a shortage of drugs needed to treat people infected with the coronavirus, including propofol, midazolam, rocuronium, cisatracurium and fentanyl.

Charette, who specializes in research in organic and pharmaceutical chemistry, believes that need could be filled if Quebec had full control over the development and production of prescription drugs, including those used during the pandemic.

And the same is true for Canada generally, he added.

“We are among the world leaders in the synthesis of small molecules,” argued Charette, who held the Canada Research Chair in Bioactive Molecular Synthesis from 2005 to 2019 and co-directs the inter-university FRQNT Research Centre in Green Chemistry and Catalysis.

“Why not take advantage of this opportunity to apply our expertise?”

Moreover, he added, having full production of drugs done here could fulfil an economic wish expressed several times by the Legault government and others in Canada: to produce locally and buy locally.

Carving out a niche

Since 2010, UdeM has carved out a niche among Canadian universities in what specialists call continuous-flow molecular synthesis. Some 50 graduate students and postdoctoral researchers have been trained in this technology over the past 10 years. Other researchers in Canada and around the world are also involved, at institutions such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Cambridge and the University of Graz.

Production of the active ingredient that makes up propofol used in hospitals, for example, can easily be done in a continuous flow process. This potent analgesic, currently widely used in the treatment of patients with COVID-19, is derived from two molecules under a special process. Traditional manufacturing methods now require large facilities to ensure mass production; the continuous flow method could help solve this problem.

The principle is simple: rather than producing large quantities of active molecules in huge reactors— some the size of a two- or three-storey building — all at once, a continuous flow of them can be made in small facilities no larger than a refrigerator. Instead of waiting until the process is complete to deliver hundreds of kilograms of molecules in a single shot, which are then converted into tablets or injectable liquid, smaller quantities can be had in a steady flow.

“This allows us to better meet demand,” said Charette. “In times of crisis, this is a key factor.”

When the desired quantity of product is reached, another active pharmaceutical ingredient can be targeted and the process re-started using a new-and improved “recipe” of manufacture, the professor added.

“Some drugs are more complex than others, but they all respond to a series of very precise procedures that only need to be applied properly," he said.

Only a few weeks

The process of synthesizing molecules in continuous flow has existed for several years in chemistry, if not decades in other fields, but the Montreal team headed by Charette has been able to exploit its potential by taking an interdisciplinary approach. Some dozen researchers are part of his group, funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, including specialists in organic, bioorganic and analytical chemistry and engineers.

The continuous-flow synthesis lab at UdeM’s chemistry department was created in 2009 with $4.4 million in funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation. For now, production capacity is limited to one or two active compounds but that number could be rapidly increased, Charette believes.

Drug preparation is a complex process. Beyond the synthesis of the active pharmaceutical ingredient, there are a number of steps to take: quality control, GMP synthesis, regulation and validation, formulation and the like. If university researchers and the pharmaceutical industry can work together to meet the challenge, Canada has a good chance of overcoming any worries of drug shortages in the near future, Charette said.

"The Americans, to name only our closest neighbour, have invested a lot in this technology,” he said. “It’s now time for us to get up to speed and position itself as a leader in continuous-flow molecular synthesis.”

Media contact

-

Jeff Heinrich

Université de Montréal

Tel: 514 343-7593