8 billion and counting: will the Earth survive?

- UdeMNouvelles

01/25/2023

The good news is that global population growth has slowed and won’t in itself cause climate change, says UdeM demographics professor Alain Gagnon.

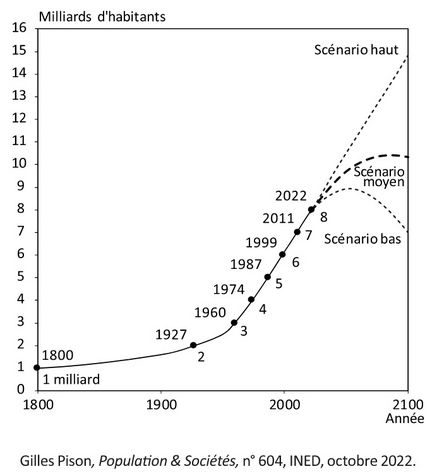

In November, the United Nations announced that the Earth is now home to eight billion people, or seven billion more than there were just 200 years ago.

How to explain this enormous leap? How will the world’s population change in the future and what repercussions will demographic growth have on the environment and climate change?

For insights, we caught up with Université de Montréal demography professor Alain Gagnon and asked him to walk us through the past, present and future of this important issue.

How did the Earth’s population reach eight billion?

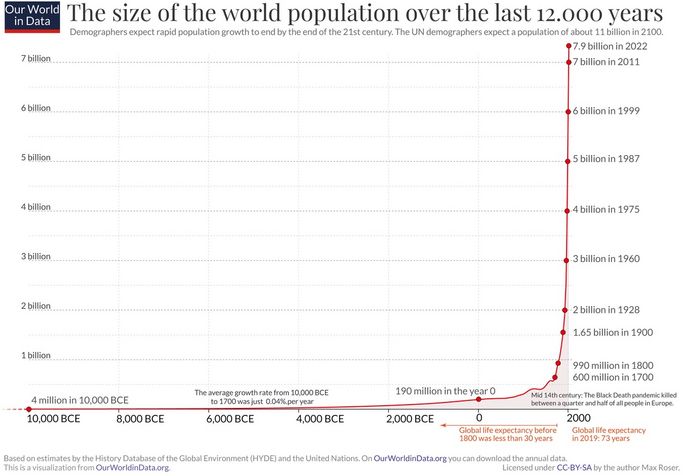

According to some estimates, there were around four million people on the planet 10,000 years ago, when agriculture was first developed. The Earth’s population grew rather slowly, only hitting 190 million 2,000 years ago.

For thousands of years, birth rates were generally higher than they are now, although the number of people on the planet fluctuated significantly due to epidemics, war, famine and other catastrophes. However, the overall growth trend was quite low.

Then the demographic curve suddenly got steeper with the Industrial Revolution, which began in the West in the 19th century. In little more than 100 years, the world’s population climbed from one billion in 1800 to two billion in 1927.

A number of factors contributed to a reduction in mortality, which is what caused this growth. These factors include better quality of life, advances in public health, medical breakthroughs (especially antibiotics), the construction of public sanitation infrastructure such as sewers, and an explosion in the production capacity of agriculture and goods and services.

After 1927, in just four decades, the world's population grew from three billion in 1960 to six billion in 1999, with the pace of growth varying from country to country. From 2000 to now, it grew by two billion people to a total of eight billion.

Although the West was the first to experience the initial stage, a decline in mortality, of what’s known as the “demographic transition” of the 19th century, it was also the first to go through the transition's second stage, a decline in birth rates. As a result, most of the recent growth has been in Asia and countries of the global South, which entered the first stage after World War II.

How will the Earth’s population change in the foreseeable future?

Low-income countries, where most of the demographic growth is expected to occur, have now entered the second stage of the demographic transition, a decline in birth rates. That’s why most experts expect the world’s population to hit a ceiling.

As for how the world's population will change by 2100, there are three demographic scenarios. The most optimistic expects us to grow to 15 billion, while the most pessimistic sees us falling by one billion. Meanwhile, what’s viewed as the most likely scenario predicts that the world’s population will plateau at 10 billion people, mostly because of lower birth rates: when a society’s quality of life improves, it produces less children.

Consequently, most of the growth in the Earth's human population has already occurred, and the expected two-billion increase won’t have as much of an effect as the seven-billion increase from 1800 to today.

Does a large global population put more pressure on the climate and the environment, and vice versa?

Scientifically speaking, we haven’t as yet found any evidence that climate change affects global demographics. Its effects on migration have already been studied, and mass migration is expected in the future, but I don’t know of any studies that measure its large-scale impact on population growth, even though we expect it will be significant in future. This is a major shortcoming in our models that has been mentioned in recent scientific conferences on population and the environment.

At the other end of the spectrum, the increase in the populations of countries with low environmental footprints does not seem critical for climate change, at least over the short term. By contrast, countries with a better quality of life, and the increased consumption that results, are already having a real impact on climate change, and have done so for some time.

So we have to look at the role that population growth will play with respect to the environment. For now, demographic growth isn’t what will have the biggest impact on our carbon footprint. The main contributing factors are our lifestyles and consumption, which are often more harmful in rich countries where birth rates are going down than they are in developing nations.