Two giants of 20th-century philosophy correspond

- UdeMNouvelles

01/16/2025

- Virginie Soffer

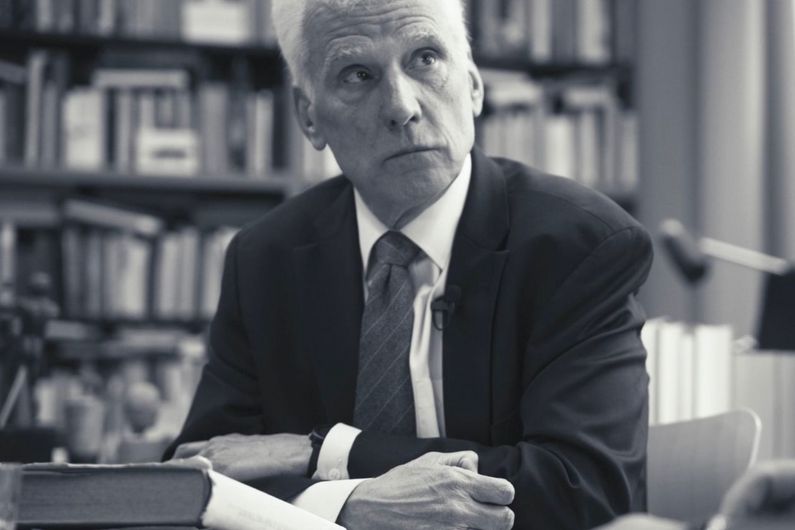

Co-edited by professor Jean Grondin, the correspondence between Martin Heidegger and his student Hans-Georg Gadamer offers unprecedented insights into their personal and intellectual relationship.

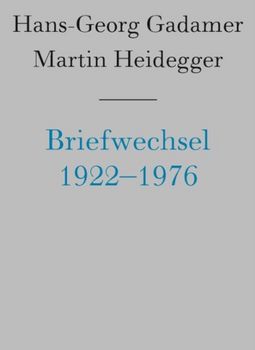

Never before in print, an extensive series of letters exchanged by Martin Heidegger and his student Hans-Georg Gadamer, two pivotal figures in 20th century philosophy, are collected in a new German-language book by the publishing houses Vittorio Klostermann and Mohr Siebeck.

The 532-page volume is edited by Jean Grondin, a professor of philosophy at Université de Montréal, and Mark Michalski, a professor at the University of Patras, and includes 219 letters written between 1922 and 1976.

The correspondence offers a unique perspective on Heidegger’s and Gadamer’s thinking, their personal relationships and their times. The volume includes 150 pages of explanatory notes and 50 pages of appendices.

Among them are Heidegger’s report on Gadamer’s dissertation in 1929, lectures Heidegger gave in Gadamer’s university classes in the 1960s, and Gadamer's letter of condolence to Heidegger's widow after his death in 1976.

We asked Grondin to tell us more about the book.

How did you come to edit this correspondence?

My connection with Hans-Georg Gadamer spans several decades. I translated five of his books from German to French and, in 1999, I published the first biography of the man. In the course of that research, I spent a lot of time in his archives. When his daughter, Andrea Gadamer, asked me to co-edit this correspondence, I agreed immediately.

I had access to the handwritten letters stored in the literary archives in Marbach, Germany. They were written over a period of 54 years, from 1922 to 1976, with some interruptions, and trace the history of the relationship between Heidegger and Gadamer and, more importantly, reveal the dynamics of their thinking, their lives and their times.

There had been talk of publishing these letters at several points in the past, but for complex reasons it never materialized. It wasn’t until recently that the project finally came to fruition, with the approval of the heirs.

What are the letters about?

The letters touch on a range of topics, both personal and philosophical. Heidegger and Gadamer discuss family matters and academic gossip, of course, but also their philosophical projects and the historical upheavals in Germany and Europe. For instance, during the Second World War, Gadamer regularly inquired about Heidegger’s situation, as Heidegger’s sons were serving on the Eastern Front. At one point, they were taken prisoner and Heidegger lost all contact with them. They were not released until several years after the war ended. Heidegger and Gadamer both lived through critical periods in German history. As we know, Heidegger supported Hitler in 1933 while Gadamer kept some distance.

Much of their correspondence was written during the war and the post-war reconstruction. Gadamer had a singular post-war experience, serving as rector of Leipzig University in the Soviet-occupied zone from 1946 to 1947. The letters from this period highlight the political tensions of the time and how the two philosophers navigated the troubled waters.

Philosophical discussions also figure prominently in their exchanges. Heidegger’s letters express keen interest in Gadamer’s publications, and Gadamer reacts to new works by his mentor. Their correspondence is useful for understanding the evolution of Heidegger’s thought over the decades. In the 1930s, he distanced himself from his magnum opus Being and Time and developed an entirely new philosophy, inspired by influences such as the poetry of Hölderlin. Gadamer followed these developments closely and incorporated them into his own work.

What did you learn from the letters?

I discovered the depth and intensity of the men’s relationship. What struck me, and even surprised me, was Heidegger’s respect for Gadamer’s work, which he never acknowledged publicly. This correspondence reveals Heidegger’s appreciation of his student’s work and reputation. We also learn that Heidegger read Gadamer’s work carefully, including the tributes Gadamer published in German newspapers on Heidegger’s milestone birthdays in 1964, 1969 and 1975.

It is clear from the letters that Gadamer regarded Heidegger as a father figure. Gadamer lost his father in 1928 when he was still relatively young. In his letters, he tells Heidegger that he saw him as a second father, intellectually speaking. The correspondence also documents Gadamer’s many visits to Heidegger.

The letters provide insight into the post-war period, particularly 1945 to 1951, when the universities were denazified and Heidegger was suspended from his post because of his Nazi past. The correspondence reflects the men’s uncertainty about their personal futures and the state of Europe.

How did you approach editing this correspondence?

As a first step, Mark Michalski and I had to decipher each man’s handwriting, which is not always easy to read. Some of Gadamer’s later letters were typed, so those were no problem, but most were handwritten.

In addition to transcribing the letters, we added annotations to clarify the context, references, people and events that were mentioned. Our goal was to make the correspondence accessible and to enrich the reader’s understanding of the 20th century while shedding light on the thought of Gadamer and Heidegger.

We also searched for missing letters. We reached out to the heirs, and Heidegger’s grandson discovered some letters among the family documents. We found more letters from Heidegger in Gadamer’s books. These discoveries were very useful for completing this volume.

We hope this publication will encourage others to share any letters they may have for inclusion in an expanded edition in the future. This would further deepen our understanding of the two men’s relationship and their times.

Hans-Georg Gadamer/Martin Heidegger: Briefwechsel 1922 bis 1976 und andere Dokumente. Aus den Nachlässen herausgegeben und kommentiert von Jean Grondin und Mark Michalski. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck / Frankfurt a.M.: Vittorio Klostermann, 2024, 532 pages. The first two dozen pages of the book, covering correspondence between 1922 to 1928 and including a table of contents, are available here.

Another scholarly book by Jean Grondin

Published in September by Bloomsbury, the 192-page Metaphysical Hermeneutics “puts forward the argument for a hermeneutical metaphysics in service of philosophy's basic aim: to make sense of our experience.” Open access to the work is funded by UdeM’s philosophy department and by proceeds from the Gold Medal that Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council awarded Grondin in 2018.