Where do we come from?

- Salle de presse

01/22/2020

- UdeMNouvelles

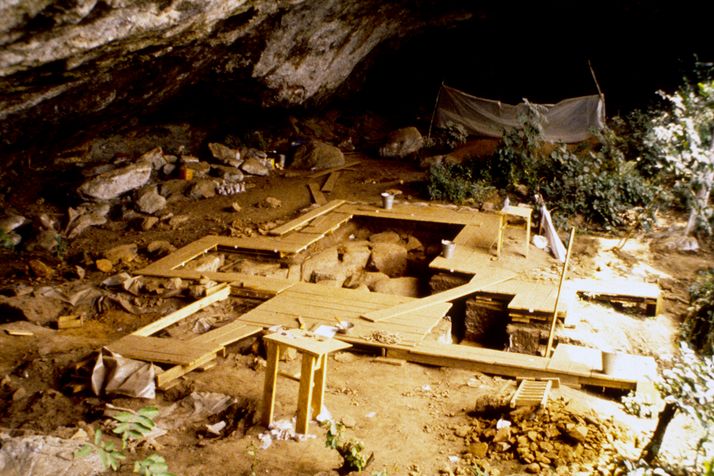

Excavation of a double burial at Shum Laka Rockshelter in Cameroon, containing the remains of two boys who lived ~8000 years ago and who were genetically from the same family. Ancient DNA reveals that these two individuals and another pair of children buried three millennia later at Shum Laka were from a stable population that was then almost completely replaced by the very different populations living in Cameroon today.

Credit: Isabelle RibotUdeM anthropologist Isabelle Ribot and an international research team look at the first ancient DNA recovered from West Africa to shed light on the origins of humankind.

Africa, the homeland of our species – Homo sapiens – harbours greater human genetic diversity than any other part of the planet. Studies of ancient DNA from African archaeological sites can thus shed important light on the deep origins of humankind. But ancient DNA studies from Africa remain few in number, in part due to the challenges of extracting DNA from degraded skeletons in tropical milieux.

Now an international research team involving Université de Montréal anthropologist Isabelle Ribot and led by Harvard Medical School scientists has come much closer to answering key questions about our origins in Africa. In a study published today in Nature, they reveal how today's Africans originate from deeply divergent, geographically separated populations, and what that means for the human species.

The scientists sequenced DNA from four children buried 8,000 and 3,000 years ago at the iconic archaeological site of Shum Laka in Cameroon, first excavated three decades ago by a team of Belgians and Cameroonians. The ancient DNA there is the first ever found in West or Central Africa and some of the oldest recovered from an African tropical milieu.

'Extremely rare'

“Shum Laka is a reference point for understanding the deep history of west-central Africa,” said Ribot, who excavated the remains of 18 people (mainly children) buried in two phases about 8,000 and 3,000 years ago. “Human skeletons are exceedingly rare here prior to the Iron Age. Tropical environments and acidic soils are not kind to bone preservation, so the results of our study are really remarkable.”

Scientists at Harvard Medical School sampled petrous (inner-ear) bones from six individuals buried at Shum Laka. Four of these samples produced ancient DNA, and were directly dated at the Pennsylvania State University Radiocarbon Laboratory. The molecular preservation was impressive given the burial conditions, and enabled whole-genome ancient DNA analysis.

None of the sampled individuals from Shum Laka is closely related to most present-day speakers of Bantu, the most widespread group of African languages. Instead, they were part of a separate population that lived in the region for at least five millennia, and was later almost completely replaced by very different populations whose descendants comprise the majority of today's Cameroonians.

Unexpected genetic diversity

The Shum Laka individuals harbored about two-thirds of their ancestry from a previously unknown lineage distantly related to present-day West Africans and about one-third of their ancestry from a lineage related to present-day central African hunter-gatherers. This indicates previously unknown genetic diversity erased over time by demographic changes caused by the spread of food production.

Analysis of whole-genome ancient DNA data from the site suggests that lineages leading to today’s central African hunter-gatherers, southern African hunter-gatherers and all other modern humans diverged in close succession about 250,000-200,000 years ago. Another set of divergences was identified to about 80,000-60,000 years ago, including the lineage of all present-day non-Africans.

'Quadruple radiation'

“Our analysis indicates the existence of at least four major deep human lineages that contributed to people living today, and which diverged from each other between about 250,000 and 200,000 years ago,” said Harvard geneticist David Reich, senior author of the study. "This quadruple radiation ... had not been identified before from DNA."

He continued: “These results highlight how the human landscape in Africa just a few thousand years ago was profoundly different from what it is today, and emphasize the power of ancient DNA to lift the veil over the human past that has been cast by recent population movements.”

The study was the result of collaboration among geneticists, archaeologists, biological anthropologists and museum curators in North America (including Harvard Medical School and the Université de Montréal), Europe (Royal Belgian Museum of Natural Sciences, Royal Museum for Central Africa, Université Libre de Bruxelles, and Saint Louis University’s Madrid campus), Cameroon (University of Yaoundé, University of Buea), and China (Duke Kunshan University), among others.

-

General view of the excavation of Shum Laka Rockshelter in Cameroon. This site was home to a human population that lived in the region for at least five millennia and bore little genetic relatedness to the people who live in the region today. Analysis of whole-genome ancient DNA data from four people who lived at this site provided insights into the relationships among several early-branching African human lineages.

Credit: Pierre de Maret

About this study

"Ancient West African foragers in the context of African population history," by Mark Lipson et al, was published Jan. 22, 2020 in Nature.

Media contact

-

Jeff Heinrich

Université de Montréal

Tel: 514 343-7593