Water quality: a matter of perspective

- Salle de presse

10/28/2020

- UdeMNouvelles

Biologists at Université de Montréal find that a common measure to assess the health of rivers can also help show the many ways their water can be used

There are so many ways to assess water quality: if you fish, your idea of “good” water is whether it supports trout, bass or walleye; if you farm, there must be enough clean water to irrigate your crops; if you’re a recreational swimmer, you like your water to be clear and safe.

Can these different points of view be harmonized? Would you drink the water you swim in, for instance, or irrigate your plants with it? What does good water quality mean, anyway, and how do we measure it?

A new Canadian study on rivers published today in BioScience provides an answer.

Led by researchers at Université de Montréal with backing from Ouranos, a Montreal-based climatology consortium, it shows that a measure called trophic status is a good indicator of its many potential uses.

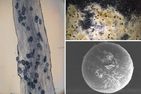

The UdeM researchers used water quality data from rivers across the country to assess their ability to provide multiple uses based on trophic status, which measures the level of nutrients in a river that supports plant growth.

Trophic status is currently widely used to determine the health of a watercourse such as a river or lake, said Nicolas Fortin St-Gelais, a postdoctoral researcher in biology at UdeM and the new study’s lead author.

Reducing nutrient inputs

When nutrients are too high in a lake, for example, excessive plant growth resulting in toxic algal blooms can occur, making the water unsuitable for recreation, irrigation and jeopardizing its drinkability. Hence, strategies to protect aquatic ecosystems often involve reducing nutrient inputs from agriculture and from sewage.

“But little is known about the extent to which nutrient reduction also protects other uses of watercourses,” said St-Gelais, whose work was supervised by UdeM biology professors Roxane Maranger and Jean-Francois Lapierre, and Robert Siron of Ouranos.

“With lower nutrient concentrations, is the quality of the water good enough to support recreational activities such as swimming and fishing, or allow farmers to irrigate, or protect aquatic wildlife? That’s what we set to find out.”

By pooling guidelines set by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment with more than 60,000 pieces of open-source data on water quality from hundreds of Canadian rivers, the researchers were able to develop a portrait of the safe uses of each river they studied.

They were also able to determine whether trophic status was a good indicator of the environment's ability to support multiple uses of the rivers’ water – a key research goal of the study.

Less safe for wildlife

“In a majority of rivers, we found that the water was safe as a source of water for livestock and swimming, whereas based on Canadian guidelines, the water was considered safe for aquatic wildlife in fewer than 50 per cent of cases,” said St-Gelais.

For water usages strongly limited by fecal contamination, such as swimming and irrigation, trophic status was to be a good indicator of water quality. It’s much less effective for protection of aquatic fauna, because trophic status is not a good indicator of heavy metal pollution.

“In essence, our study tries to look at water quality from different worldviews and tries to see if people who assess it through a public health and the agricultural perspective see the problem in a different way as compared to ecologists,” said Maranger, senior author of the study.

“The answer is there are some strong interrelationships,” she said.

“And we think that looking the problem of water quality more holistically – and respecting that there are many different ways of seeing the same problem – will help develop the understanding needed to support more sustainable decisions made by policy makers, over the long term.”

About this study

“Evaluating trophic status as a proxy of aquatic ecosystem services provisioning on the basis of guidelines,” by Nicolas St-Gélinas et al, was published Oct. 15, 2020 issue of BioScience.

Media contact

-

Jeff Heinrich

Université de Montréal

Tel: 514 343-7593