What do the slogans at demonstrations tell us?

- UdeMNouvelles

09/30/2022

- Béatrice St-Cyr-Leroux

Sociologist and UdeM professor Cécile Van de Velde has analyzed text from seven major protests around the world to understand the voices of contemporary social movements.

We see them on banners, hand-held signs, walls, clothing, bodies and faces: words are central to social protest. Every slogan—collective or individual, printed or handwritten, demand or rallying cry—conveys a political message and an expression of anger.

Are there patterns in the words of protest found across social movements and across borders? Are there common themes? In short, what can the words tell us about the movements?

Cécile Van de Velde, professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Montreal and the Canada Research Chair in Social Inequalities and Life Journeys, has been probing this question for more than 10 years.

She was initially interested in young people and their political engagement. Now she has published a study of “contemporary grammars of anger” that investigates the roots, forms and dynamics of the vocabulary of protest.

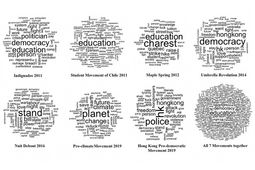

Her research is based on observation and compilation of the “anger words” contained in the slogans, signs and texts of seven social movements propelled by young people between 2011 and 2019: the “Indignados” anti-austerity demonstrations in Madrid (2011-2012), the student movement in Santiago, Chile (2011-2012), the Maple Spring student protests in Montreal (2012), the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong (2014), the “Nuit debout” demonstrations against labour reforms in Paris (2016), the climate march in Montreal (2019), and the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong (2019).

Humanistic principles and emotions

Van de Velde found that the slogans written on the signs and chanted by demonstrators were appeals to fundamental values more than condemnations. Contrary to what is often said, the social movements she studied were much more “pro” than “anti,” advocating big ideas such as democracy, education and inter-generational justice.

“Over the years, I’ve noticed a rise in generational discourse, in which young people directly accuse previous generations of unfairly leaving them a grim social, economic, political and environmental legacy,” said Van de Velde. “The young demonstrators are worried about their future: will they be able to study without sinking into debt, make their voices heard, make choices about their lives, have a say in collective decisions?”

Amidst the messages of revolt and anger, Van de Velde also discerned hope. “The young protesters speak with optimism; you need hope to revolt,” she commented. It was in Montreal that she saw the most hope, both during the Maple Spring and in the climate march.

While anger and hope seem to be the dominant emotions in the slogans, Van de Velde also found a good measure of sadness, despair and joy, particularly joy in standing together.

Why dwell on angry words?

Van de Velde has always been interested in researching social anger, which she considers an important emotion for understanding the evolution of democracies. In her view, demonstrations are the quintessential sites for expressions of anger, and for meeting the people who express it.

“Social movements can give voice to those who are normally silent, to young people who are rarely represented in the media, who don’t vote,” she said. “And I’m captivated by that diversity and expressiveness.”

Van de Velde’s studies of this “invisible” fringe of society have shown an evolution in the language of revolt. The slogans are increasingly individualized and personalized: people are making “I” statements about their own experience to reinforce the “we” of the movement.

“Protest texts aren’t just words, they are political performances,” Van de Velde observed. “Analyzing them gives us a better understanding of contemporary revolt.”