Who are the sexual abusers?

- UdeMNouvelles

11/14/2022

- Béatrice St-Cyr-Leroux

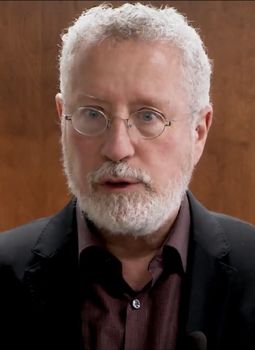

Psychologist Jean Proulx, a professor from School of Criminology, has been working for more than 30 years to demystify the process that leads up to sexual assault and find ways to prevent recidivism.

When people read a story in the newspaper about a woman being brutally raped or a little boy repeatedly sexually abused, they have a visceral reaction of revulsion and anger.

Jean Proulx feels the same way. But the professor in the University of Montreal’s School of Criminology also asks himself the question: What drove this person to commit these terrible deeds? What was his motivation? Can he be prevented from reoffending?

Proulx is an authority on the process that takes sexual offenders—be they pedophiles, rapists or murderers—from thought to action. More specifically, he studies the links between the sexual abuser’s M.O., personality and lifestyle.

For 10 years, Proulx worked full-time treating sexual offenders as a psychologist at the Institut Philippe-Pinel, a psychiatric hospital for the criminally insane. Today, he still visits the hospital once a week to interview inmates and try to understand what induced them to commit their offences. Most importantly, he is interested in risk-mitigation strategies.

Different but similar

While the profiles of sexual abusers are varied, as are their victims (women they don’t know, children, teenagers, spouses, a combination), Proulx believes all sexual offenders have personality disorders.

In his book Pathways to Sexual Aggression, published in 2014, Proulx unpacks the processes that lead men to sexually assault children or women. He describes various groups and subgroups of abusers, including three that had not been previously studied (marital rapists, hebephilic sexual abusers and polymorphic sexual abusers).

For example, he found that pedophiles are often avoidant and have low self-esteem. They feel rejected by adults and welcomed by children, who seem warmer and more accessible.

Many abusers of women are antisocial narcissists and/or have borderline personality disorder, in which violence and outbursts of rage stem from an inability to contain emotions and control impulses. According to Proulx, intrafamilial abusers (men who assault their spouses or ex-spouses) are often the most violent and angry, seeking absolute control.

Among sadists, who enjoy torture or mutilation, schizoid and avoidant personality disorders are common. Sadists make up a large proportion of sexual murderers. They are more likely to be extrafamilial than intrafamilial aggressors.

Understanding in order to treat

It is because he sees the human being behind the crime and wants to prevent recidivism that Proulx has devoted so many years to understanding dangerous criminals.

“People who commit serious sexual offences have had difficulties in their lives and didn’t know how to deal with them,” he said. “Sexual offences were a coping strategy for them—not a good one, obviously. So we need to identify the risk factors and mitigate them. For example, if it’s social anxiety or anger, we’ll work on managing emotions or do cognitive work to see if social situations are being correctly interpreted or try to find socially acceptable ways to express anger.”

The approach seems to be working. It is believed that untreated sexual offenders have a recidivism rate of approximately 17%; with risk-factor-based support, the rate is between 3 and 8%.

“I feel I’m helping them with my research and my practice at the Philippe-Pinel institute,” said Proulx. “If I treated them like garbage, it wouldn’t help them get better and the recidivism rate would stay at 17%. You have to look at the human being, not the crime.”