The under-education of men: a deepening problem

- UdeMNouvelles

04/21/2023

- Martin LaSalle

Women outnumber men in higher education. While more women in university is welcome news, the under-representation of men is worrisome, according to a new book.

Women’s enrolment in higher education has increased significantly in the past 70 years in both Quebec and Canada as a whole.

In the early 1950s, only 22 per cent of students enrolled in Canadian universities were women. Since then, that number has risen slowly but steadily: in 2020, 57 per cent of university students were women. The trend in university graduation rates is similar.

While the goal was to reach gender parity, women started to outpace men in university enrolment and graduation rates in the 1990s, and since then the gender gap has only widened in what appears to be a long-term trend.

This trend cannot be explained by women “taking the place” of men – in fact, the causes are varied and deep-rooted, according to a new French-language book published March 28 by Les Presses de l’Université de Montreal.

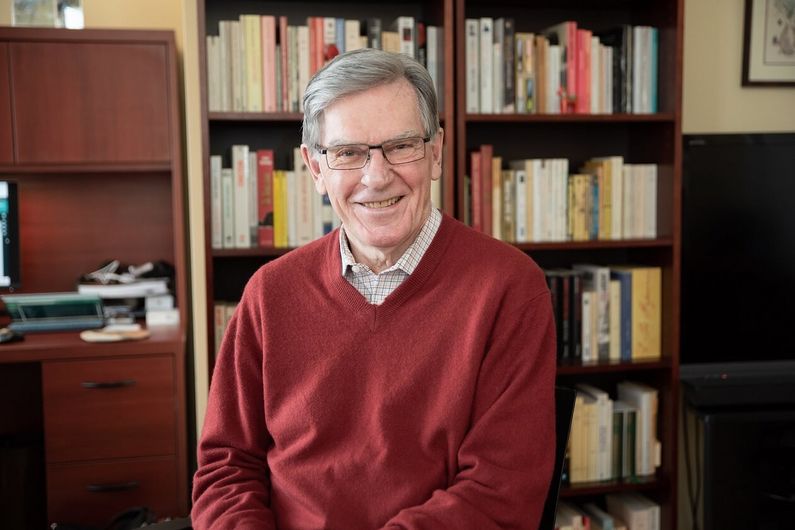

La sous-scolarisation des hommes et le choix de profession des femmes is written by lead author Robert Lacroix with professors Catherine Haeck, Richard Ernest Tremblay and the late Claude Montmarquette.

We asked Lacroix, rector emeritus of Université de Montréal, about the under-education of men, its consequences and what can be done about it. While the conversation focused on the first part of the book, the second part is equally fascinating: it looks at women’s career choices.

What led you to conclude that men are under-educated compared to women?

Lacroix: Data collected in both Canada and other countries show that women’s enrolment in university has increased in recent decades. Our analysis of anonymized data for a cohort of students at Université de Montréal and its affiliated schools, HEC Montréal and Polytechnique Montréal, also confirmed the hypothesis that women have access to more programs than do men when they enroll because of their higher grades, and once enrolled they outperform men.

In 1992–1996 in Quebec, women earned 56.6 per cent of bachelor’s degrees, 52 per cent of master’s degrees and 36 per cent of Ph.Ds. By comparison, in 2018, women earned 61 per cent of bachelor’s, 60 per cent of master’s and 52 per cent of Ph.Ds.

The trend is similar at Quebec’s cégeps: in 2018–2019, women made up 57.3 per cent of enrolled students and 61 per cent of graduates.

It is important to note that this gender gap in education is not unique to Canada; it also exists in the 15 or so European countries for which we obtained data.

What is the cause of this gender gap in university enrolment and graduation?

Lacroix: The data show that this gap has existed for a long time. For example, in 1954–1955, the pass rate for Quebec ministerial exams in primary school (then given in Grade 7) was 72 per cent for boys and 77 per cent for girls. Data for 1962–1963 show that 44 per cent of boys in primary school had fallen behind academically, compared with 33 per cent of girls. This problem was still present in 1997–1998, affecting 25 per cent of boys and 17 per cent of girls.

It appears that the problem begins well before secondary school. A 1999 report by Quebec’s Conseil supérieur de l’éducation suggested that the underlying cause is different attitudes towards school and success: girls just like school more than boys do. Results from the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) surveys of 15-year-olds point to a number of behaviours that could explain boys’ weaker academic performance: they are less likely than girls to read for pleasure, to do their homework, to arrive at school on time and to be intrinsically motivated by their studies.

This could help explain why in 2018–2019, the dropout rate for Quebec high-school students enrolled in the general studies program was 17.8 per cent for boys compared with 10.7 per cent for girls. The graduation rate was 90 per cent for girls versus 78 per cent for boys in 2016–2017, a 12-point gap.

In our book, we take a deeper look at this gender gap by examining the results of longitudinal studies, including ones conducted by UdeM's Richard Tremblay in Quebec. These studies show that starting at 17 months, girls cognitive development is more advanced than that of boys, and so they enter kindergarten and Grade 1 better equipped to succeed in formal schooling. This could be the root cause of later gender differences in achievement. We also use and replicate other longitudinal studies to better understand this gender gap and propose solutions.

Why is the under-education of men so worrisome and what are the potential consequences?

Lacroix: The academic delays that begin in primary school – and perhaps even earlier – affect boys’ performance in high school and their likelihood of graduating. This in turn puts them at a disadvantage in post-secondary studies, affecting university enrolment and graduation rates.

According to the human capital theory in economics, through education people can increase their productive capacity as workers and earn higher salaries.

This is in fact borne out by studies: 2018 data for OECD countries show that workers with a bachelor’s degree earned on average 44 percent more than those with a high school diploma. The number climbed to 91 per cent for those with a master’s or Ph.D. degree.

Educational attainment also affects employability. The same 2018 OECD data show that the employment rate for 25- to 34 year-olds who hadn’t completed high school was 60 per cent, compared with 78 percent for those with high school or post-secondary education, and 84 per cent for those with a university education.

In their university studies, women have a wider choice of disciplines and are more likely to be accepted into programs with limited enrolment. By contrast, men are more likely to be limited to their second or third choice of program when they enrol. They are also more likely to interrupt their studies due to lower grades or lack of interest in the disciplines open to them. In short, women are more able to study in the field they choose and in which they want to work.

Another, and by no means negligible, issue is the loss of jobs due to automation. The OECD estimates that 14 per cent of workers are at high risk of seeing their current duties become automated within the next 15 years, while another 30 per cent will see significant changes in their tasks and, therefore, the skills required to do their job.

However, less than 5 per cent of workers with a university degree are at high risk of losing their job due to automation, compared with 40 per cent of those with only a high school diploma. And having a higher level of education makes it easier for a person to go into another line of work if they must.

And education provides vast benefits beyond its economic and social impact. It is a transformative process that opens up realms of knowledge to the learner and forever changes the person and their relationships with others and society as a whole. The gender gap in education, which is already wide and growing, can be expected to have consequences in this respect as well.

What solutions can you suggest?

Lacroix: We propose a number of solutions. In general, they focus on the long term because there is no quick fix. We can’t help men succeed in university and graduate if they aren’t in university.

We have to start intervening very early, even in the womb – for example, through home visits to screen for nutritional deficiencies, infectious diseases, and neurotoxins and other substances that can affect the unborn child. Quebec's Olo Foundation prenatal nutrition program is a good example.

Intervention during the preschool years is also important. Research has shown that preschool programs for disadvantaged children, including Quebec’s daycare system, have numerous long-term benefits. We should ask ourselves why this model doesn’t reach disadvantaged families as much as it should.

At the primary and secondary levels, we need to rethink the practice of having children repeat a grade. Quebec has the highest rate of grade repetition in the country, and yet the results of the 2018 PISA suggest this strategy does not improve academic performance and perseverance in the majority of children who repeat.

It would also be beneficial – and cost little – to adapt high-school schedules to the circadian rhythm of teens. And we think it is time for Quebec to make school compulsory up to age 18 or until a high-school diploma or equivalent has been earned, as is the case in Ontario, Manitoba and New Brunswick.

We make many other recommendations in our book, particularly with respect to post-secondary education.

In sum, solutions exist and we hope our book will raise awareness among the many people involved in education, including politicians, about the harmful effects of the under-education of men. We hope it will prompt them to make this issue a priority and finally take concrete action.