Tiny hitchhikers: scientists uncover new "mini-satellites" in sea bacteria

- UdeMNouvelles

01/24/2024

In an unseen process playing out in the deep, miniature elements of DNA are quietly outsmarting viruses.

Microbiologists led by Université de Montréal's Frédérique Le Roux have made an underwater breakthrough, discovering what they're calling "mini satellites" in sea bacteria.

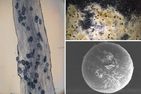

These tiny genetic elements, known as phage-inducible chromosomal minimalist islands (PICMIs), are changing the way scientists think about life in the ocean.

"Imagine a tiny piece of DNA that can't move on its own," said Le Roux, holder of a Canada Excellence in Research Chair, whose international study is published this week in Nature Communications.

"The DNA needs a virus, called a phage, to travel around. These are known as phage satellites. Phages usually attack bacteria, but these satellites are like smart hitchhikers, using phages for free rides."

In their study, Le Roux and her co-researchers in France and Spain found that PICMIs depend heavily on their phage partners. They need specific phages to wake them up and start their journey. "What's fascinating is that while many satellites interfere with their phage hosts, PICMIs do this less, showing a more harmonious relationship," said le Roux.

These tiny elements are not just rare oddities; they're found in a variety of Vibrionaceae bacteria, a family that includes some well-known characters like Vibrio cholerae. The team's detective work in bacterial genomes revealed that PICMIs are quite common in these marine bacteria.

Small and simple

PICMIs are special because they're incredibly small and amazingly simple. They don't change the shape of their phage "taxis" and can pack their DNA in a unique way. They sneak into the bacterial genome, right next to a key gene, and carry only a few essential tools for cutting and pasting themselves into and out of the bacterial DNA.

And PICMIs are quite clever. They don't mess with the phages that carry them, meaning they can spread without causing trouble. Plus, they have another trick up their sleeve: they can protect their bacterial host from other bad phages, making them a kind of microscopic bodyguard.

Perhaps the most exciting part is the discovery of a new defense system in PICMIs. They've got a gene, called up2, that helps their bacterial host fight off certain phages. This is like having a secret weapon against unwanted intruders, showing how complex and fascinating the micro-world in our oceans can be.

"In short, the discovery of PICMIs is like finding a new piece in the puzzle of ocean life," said Le Roux, who a new professor in UdeM's Department of Microbiology, Infectious Diseases and Immunology.

"Our findings tell us more about the tiny battles and alliances happening under the sea, where bacteria, viruses, and these mini satellites play a crucial role. This research isn't just a scientific curiosity; it could help us understand more about the ocean's ecosystem and even inspire new ways to tackle bacterial infections."

About this study

"Phage-inducible chromosomal minimalist islands (PICMIs), a novel family of small marine satellites of virulent phages," by Frédérique Le Roux et al., was published Jan. 22, 2024, in Nature Communications.

Media contact

-

Jeff Heinrich

Université de Montréal

Tel: 514 343-7593