A risky mix of two diseases

- UdeMNouvelles

02/29/2024

Stéphanie Forté and co-researchers in Canada and Brazil have shown how people with sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait have a higher chance of dying from COVID-19 than the general population.

Patients with sickle cell disease and carriers of the sickle cell trait, often considered benign, face higher rates of death and hospitalization if they contract COVID-19, a new Canada-Brazil study suggests.

Led by Université de Montréal assistant medical professor Dr. Stéphanie Forté, the meta-analysis is published in the open-access journal eClinicalMedicine, part of The Lancet Discovery Science.

Though not frequently talked about, sickle cell disease is the most common rare disease in Canada, affecting nearly 6,000 people, mostly of African, Caribbean, Indian or Middle Eastern origin.

“In Quebec, an estimated 1,500 to 1,800 people have it,” said Forté, a hematologist and researcher at the UdeM-affiliated CHUM Research Centre.

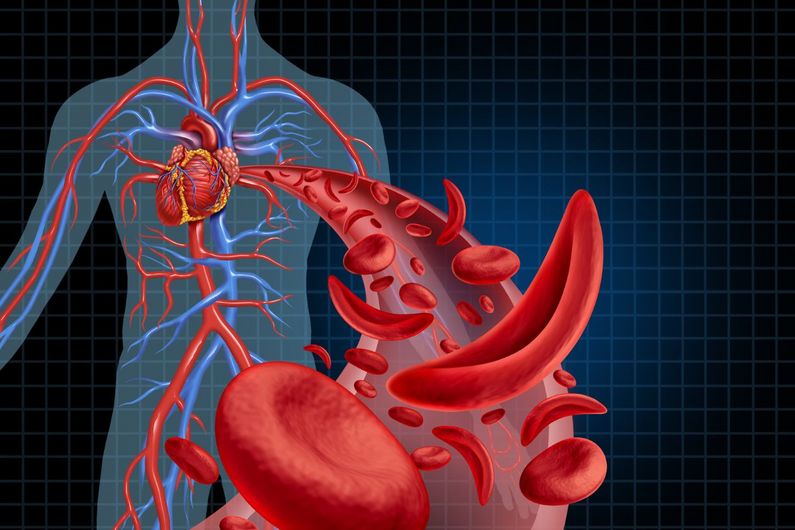

A hereditary chronic illness, the disease is characterized by rigid red blood cells that lead to blockages in the blood vessels, depriving muscles and organs of oxygen and causing severe recurring pain or sequelae in various organs.

To date, there is no approved treatment specifically for sickle cell disease in Canada.

Hydroxyurea, an oral chemotherapy drug, has been used safely for over 40 years as a preventive treatment that reduces the number of episodes, protects organs and prolongs life expectancy.

Hydroxyurea makes red blood cells rounder and more flexible by increasing a protective form of haemoglobin, haemoglobin F. This haemoglobin is also called fetal haemoglobin because newborn babies have it.

To alleviate episodes of severe pain, patients resort to pain-relief medications, emergency care and hospitalization. Some patients with more severe disease depend on regular blood transfusions.

“Carriers of the sickle cell trait have only one of the altered, recessive genes from their parents and don’t develop sickle cell disease,” said Forté. “Nevertheless, this group is at risk and should be monitored and prioritized when it comes to public health measures, like vaccination.”

These people are also more susceptible than the general public to renal complications following a COVID-19 infection.

Lessons from 2009

It was no coincidence that Forté and her colleagues decided to evaluate the impacts of SARS-CoV-2 on people with sickle cell disease. Back in 2009, during the H1N1 flu pandemic, medical teams had concluded that, globally, patients with sickle cell disease had a higher risk of developing acute chest syndrome or of being admitted into intensive care.

In 2020, while on a foreign fellowship at the Henri-Mondor Hospital in Créteil, France, Forté witnessed the setting up of that country's register of people with both sickle cell disease and COVID-19.

“When I returned to Quebec, at the height of the pandemic, I launched our own Quebec register, with Dr. Thai Hoa Tran’s team at the CHU Sainte-Justine research centre,” she recalled. “All of the Quebec sickle cell disease centres collaborated on this project.”

In 2022, the initiative to study the link between sickle cell disease, sickle cell trait and COVID-19 came from Isabella Michelon, a Brazilian medical student at the Catholic University of Pelotas. For one of her epidemiology courses, Michelon contacted international teams who were conducting research on sickle cell disease and COVID-19. Forté’s team answered her call.

With Michelon as the first author, a large-scale effort was undertaken to collect and analyze 22 studies in a meta-analysis, including nearly 1,900 people with sickle cell disease, 8,700 people with the sickle cell trait and over 1.65 million control patients.

'Wonderful recognition'

Forté is the medical lead of the CHUM’s Comprehensive Red Blood Cell Disorders Centre (SANGRE). The centre was recently selected by the American Society of Hematology to receive mentorship and support over two years as part of the Sickle Cell Disease Centers Workshops.

“It’s a wonderful recognition,” said Forté. “By being a part of this network of excellence, we are able to compare our performance to other establishments and to benefit from workshops on best practices in our field. At the CHUM, our top priority is to work to provide better relief for our patients suffering from severe pain.”

She is grateful to the patients who are a part of the register, and additionally, for their donations to the blood biobank, which to date comprises 300 samples and which was established in collaboration with her mentor, UdeM professor Guillaume Lettre, a researcher at the Montreal Heart Institute.

In 2006, Lettre discovered that the severity of sickle cell disease was linked to variations in the BCL11A gene. BCL11A plays a role in silencing the expression of the fetal haemoglobin after birth. His fundamental research work led to the first experimental treatment for the disease, developed by an American pharmaceutical company, to inactivate the BCL11A gene.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently approved this gene therapy, which is based on CRISPR-Cas9, molecular "scissors" that inactivate BCL11A. Though expensive, the treatment marks a significant advance for people with sickle cell disease.

About this study

“COVID-19 outcomes in patients with sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait compared with individuals without sickle cell disease or trait: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” by Isabella Michelon under the supervision of Stéphanie Forté and her colleagues, was published Dec. 8, 2023, in eClinicalMedicine.