Prostate cancer: treating it early for a better, longer life

- UdeMNouvelles

11/09/2020

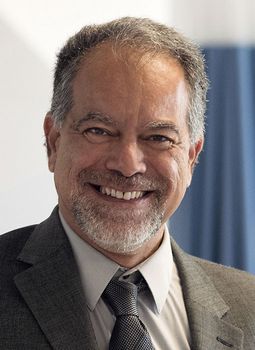

Dr. Fred Saad, an UdeM medical professor and principal scientist at the CHUM research centre, reviews several of his recent studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The medical field of prostate cancer has produced a wealth of doctors and researchers whose work has led to major scientific advances in treatment of the disease. Université de Montréal medical professor Dr. Fred Saad is one of these exceptional physicians.

Chief of urology at the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, holder of the UdeM’s Raymond Garneau Chair in Prostate Cancer Research and principal scientiist at the CHUM’s research centre, Saad is active on the front lines of clinical and research approaches to prostate cancer.

He has collaborated on the discovery of practically all new treatments for the disease in the last 25 years and is one of the most highly consulted specialists worldwide. His work is now mainly focused on molecular prognostic markers and new therapeutic approaches for advanced prostate cancer.

Saad co-led the 2018 PROSPER study, an international clinical trial that showed that enzalutamide, a drug used to treat non-metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer, delays the development of metastases in patients for about two years.

Here, he discusses the most recent data from that study and some others recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The new PROSPER data show that enzalutamide also improves patients’ overall survival. How so?

We use the term ‘castration-resistant’ when a patient’s cancer progresses despite hormone therapy. We are alerted when the patient’s PSA (prostate-specific antigen) levels increase quickly. When patients fail this type of therapy, they don’t die of old age with prostate cancer; they die of prostate cancer.

In our most recent study, we showed that the use of enzalutamide a year and a half prior to the development of metastases in these patients gives them nearly one additional year of survival time, compared to treatment initiated once the metastases have developed. Enzalutamide is an anti-androgen therapy that prevents prostate cancer cells from using testosterone to grow.

So we delay these patients’ death and the development of metastases. Compared to patients who have developed metastases, patients treated with enzalutamide are three times more likely to survive.

The message here? Early treatment really makes a difference.

In SPARTAN, another international study that I co-led, we also showed that with apalutamide (which has the same therapeutic target as enzalutamide), starting treatment early was not only beneficial for asymptomatic patients, but also that their quality of life was preserved despite the use of this type of drug.

Is it possible to treat men with mutations of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes to slow the progression of the disease and increase their chances of survival?

Yes, absolutely. My colleagues and I show this in two recent international studies (called PROfound) published in the NEJM. These studies are the first concrete examples of the use of personalized medicine in the treatment of prostate cancer.

In women, mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Also present in some men, these mutations expose them to an increased risk of highly aggressive prostate cancer.

We tested 4,000 men and enrolled 400 men with castration-resistant metastatic cancer and at least one faulty BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM or other DNA repair gene.

In patients treated with olaparib, a PARP inhibitor, we observed a near 60-per-cent delay in disease progression and reduction of more than 30 per cent in mortality. PARPs are enzymes that help repair damage done to DNA. By blocking them, olaparib prevents the cancer cells from undergoing repairs, causing them to die.

Today, patients receive genomic testing at the time of diagnosis via biopsy and the analytical results are not immediately available. In the near future, with technological advances, it is reasonable to imagine that this type of tool will be available to clinicians, allowing them to begin treating patients with advanced cancers earlier.

About the CRCHUM

The CHUM Research Centre (CRCHUM) is one of North America’s leading hospital research centres. It strives to improve the health of adults through a continuum of research spanning disciplines such as basic science, clinical research and population health. More than 2,150 people work at the CRCHUM, including nearly 500 researchers and nearly 650 students and postdoctoral fellows. crchum.com