The world’s first photographically illustrated book is at UdeM

- UdeMNouvelles

04/19/2022

- Virginie Soffer

Botanist Anna Atkins was the first person in the world to publish a book illustrated with photographs. A precious copy of the volume is in UdeM’s rare books collection.

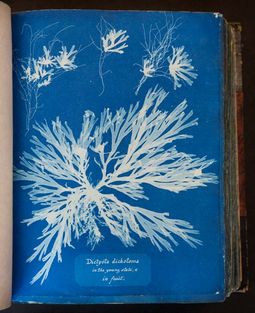

The world’s first book illustrated with photographic images was a scientific work entitled Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. It was produced by a woman, botanist Anna Atkins. Although it was published in fascicles, each containing only a few images of algae, the University of Montreal has an exceptional copy containing 455 plates.

The volume has been restored in recognition of the Fondation Courtois’ gift to the University.

A new technique

Forgotten today, Anna Atkins was a pioneer of photography in Victorian England. She was a brilliant botanist and a member of the Botanical Society of London, one of the few learned societies that admitted women at the time. She had learned to paint faithful watercolours of plants but when a new photographic printing technique, the cyanotype, was developed, she leaped on it as a way to depict plants even more accurately. Invented by John Herschel in 1842, the technique uses the sensitivity of iron salts to light in order to produce images on paper.

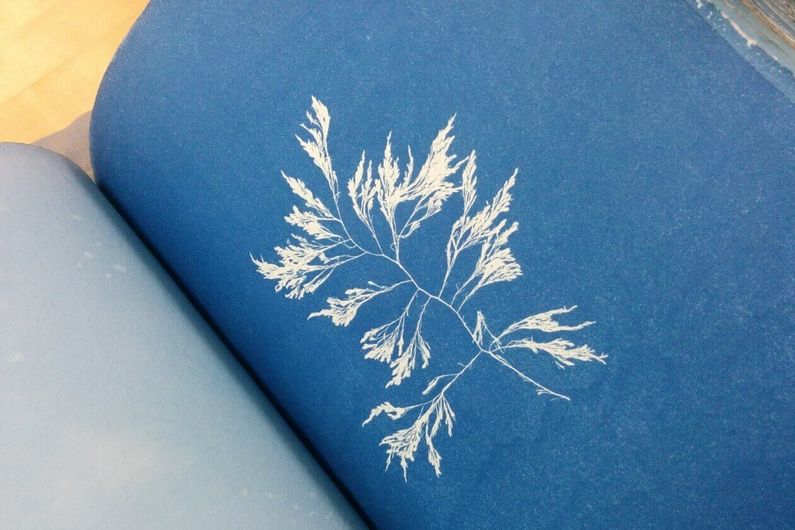

Anna Atkins produced the impressions in the book by placing algae on sheets of paper coated with a solution of potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate. She then placed the sheets under glass and exposed them to light. The salts reacted to the sunlight and a yellow image appeared. After the sheets were washed with water and then dried, the iron compounds reacted and the yellow changed to a deep Prussian blue.

Technique meets art

Looking at the plates, one is struck by the delicate beauty of the algae against the vivid blue backgrounds. It’s a stark contrast with traditional plant drawings and botany books, in which plants are habitually shown against a white background. Here, the algae seem to be floating in air or the sea. As if in a dream, they have been transformed from earthy brown to an ethereal white. But they don’t look like faraway ghosts: every detail is distinct. We can see the smallest filament, drifting gently, now frozen in eternally suspended time. Each panel looks like a work of modern art—in the University of Montreal’s colours!

“The way the algae are arranged contrasts with the usual scientific composition you find in a herbarium,” said Normand Trudel, librarian in UdeM’s Rare Books and Special Collections Library. “The concern with aesthetics is immediately apparent. More than the scientific aspect, it is the beauty of these images against a deep blue background that still strikes us at first glance.”

Unique plates printed over a 10-year period

Whereas photography produces a negative from which many prints can be made, a cyanotype produces only one print. Each sheet is manually coated with iron salts and each receives a unique imprint. Anna Atkins made thousands of prints of algae, which she distributed in fascicles between 1843 and 1853. She assembled a first volume in 1843 and subsequently added two others.

Some institutions have some of the fascicles or one or two of the volumes in their collection. Very few have all three volumes in one place. The New York Public Library and the University of Montreal are among the only institutions to have almost all the plates.

UdeM’s exceptional copy

According to Professor Larry J. Schaaf, a leading expert on Anna Atkins’ work, and Joshua Chang, a curator at the New York Public Library, the copy held at UdeM’s Rare Books and Special Collections Library is one of the most complete and interesting in the world. They came to examine it in 2017, and it was subsequently featured in an exhibition and international symposium on Anna Atkins at the New York Public Library in 2018.

According to a handwritten note inserted in the book, the cyanotypes it contains were bequeathed by Anna Atkins as loose plates to Margaret Brodie, the widow of John Herschel, the inventor of the cyanotype. Around 1880, Margaret Brodie’s son had them bound.

Was the book acquired by Marie-Victorin?

The University of Montreal’s copy comes from the UdeM Botanical Institute’s collection. The Institute was founded by Brother Marie-Victorin in 1920 and he oversaw the collection. Did he himself purchase the book? Did the Institute receive it as a gift? We know that between 1938 and 1944 Marie-Victorin made seven trips to Cuba to study biodiversity on the island and part of his research was supported by a certain Atkins Foundation. But this turns out to be a false lead because it was actually a different Atkins family. However, it is possible that it was through this foundation that Marie-Victorin came into possession of the book. His correspondence would have to be searched to try to unravel the mystery of how the volume made its way from the Herschel family to the Botanical Institute.

The book was recently digitized and will soon be available online on the University of Montreal Library’s Calypso platform.

Restoration of the book

To be coated with iron salt and produce cyanotypes, each sheet of paper must be quite thick. You can’t use Bible paper! So, at more than 400 pages, the book has some heft. Over the years, the weight took its toll on the binding. A restorer was brought in to reglue it.

The University of Montreal dedicates the restoration of this beautiful document in the Rare Books and Special Collections Library to the Fondation Courtois as a token of appreciation for their extraordinarily generous gift to the University.