Tick-borne diseases: Tracking anaplasmosis

- UdeMNouvelles

08/01/2022

- Béatrice St-Cyr-Leroux

A research team from UdeM’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine is investigating the source of anaplasmosis, an emerging tick-borne disease.

Residents of the Eastern Townships have known about Lyme disease for years, but now they must beware another disease carried by blacklegged ticks: anaplasmosis. Last summer, 35 cases of the flu-like illness were reported in the Eastern Townships, the most in any location in Canada.

Anaplasmosis could become increasingly common in Quebec, partly because climate change is extending the ticks’ period of activity, accelerating their life cycle and hence prolonging human exposure to the ticks.

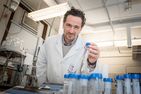

The upward trend has caught the attention of a research team at the University of Montreal’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. This summer, professors Catherine Bouchard, Cécile Aenishaenslin, Patrick Leighton and Jean-Philippe Rocheleau, along with Raphaëlle Audet-Legault, a veterinarian and master’s student in epidemiology at UdeM, are conducting research to determine which species of small wild mammals are reservoirs for anaplasmosis and therefore contributors to human transmission of the disease.

“The tick is like a used syringe,” explained Bouchard. “Let’s say it bit a mouse for its previous meal. Suppose the bacteria responsible for anaplasmosis was circulating in the mouse’s blood stream. Now, when the tick bites a human, it infects him with the mouse’s blood. If the mouse was carrying a zoonotic variant, the human will become infected with the disease.”

Mapping distribution

With help from the town of Bromont, the Estrie Public Health Department and the Brome-Missisquoi Regional County Municipality, the team will capture rodents of different sizes (mice, chipmunks, squirrels) around Bromont over the summer to see which ones have the highest prevalence of anaplasmosis. The veterinarians will also collect ticks in the field to measure the proportion of infected ticks in the area.

Half of the sampling sites are in areas where there have been human cases and the other half where there have been none. “We want to compare the proportion of infected small mammals in the vicinity of human cases and farther away, in addition to determining whether the prevalence of infection varies by species,” said Audet-Legault.

“We’re interested in the extent to which circulation of the bacterium is contained,” added Bouchard. “I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s no difference between the sites near human cases and the others. We may find that there are more human cases where there’s higher population density but the disease is equally present elsewhere. So residents would need to exercise due vigilance.”

Education for prevention

In view of the explosion of human cases of anaplasmosis, efforts to promote safe behaviours in exposed populations—such as full-length clothing and routine self-inspection after going outdoors—should be stepped up, said Bouchard.

The education efforts should be directed not only at residents but also health professionals, who should look beyond Lyme disease when diagnosing patients from high-risk areas.

Anaplasmosis is not easily diagnosed because the symptoms are generally non-specific and mild, such as fever, chills, headache and muscle pain. Unlike Lyme disease, the tick bite leaves no redness on the skin.

Audet-Legault also pointed out that most humans infected with anaplasmosis are bitten near their homes, while gardening or engaged in similar activities. “In the Eastern Townships, many people have homes on the mountainside, under a canopy of mature trees. So they’re literally living in the tick’s habitat. We need to increase our awareness-raising efforts, since all residents are potentially at risk.”

As a first step, the research team has met with Bromont residents to present their research project. Interactive workshops are planned over the summer.