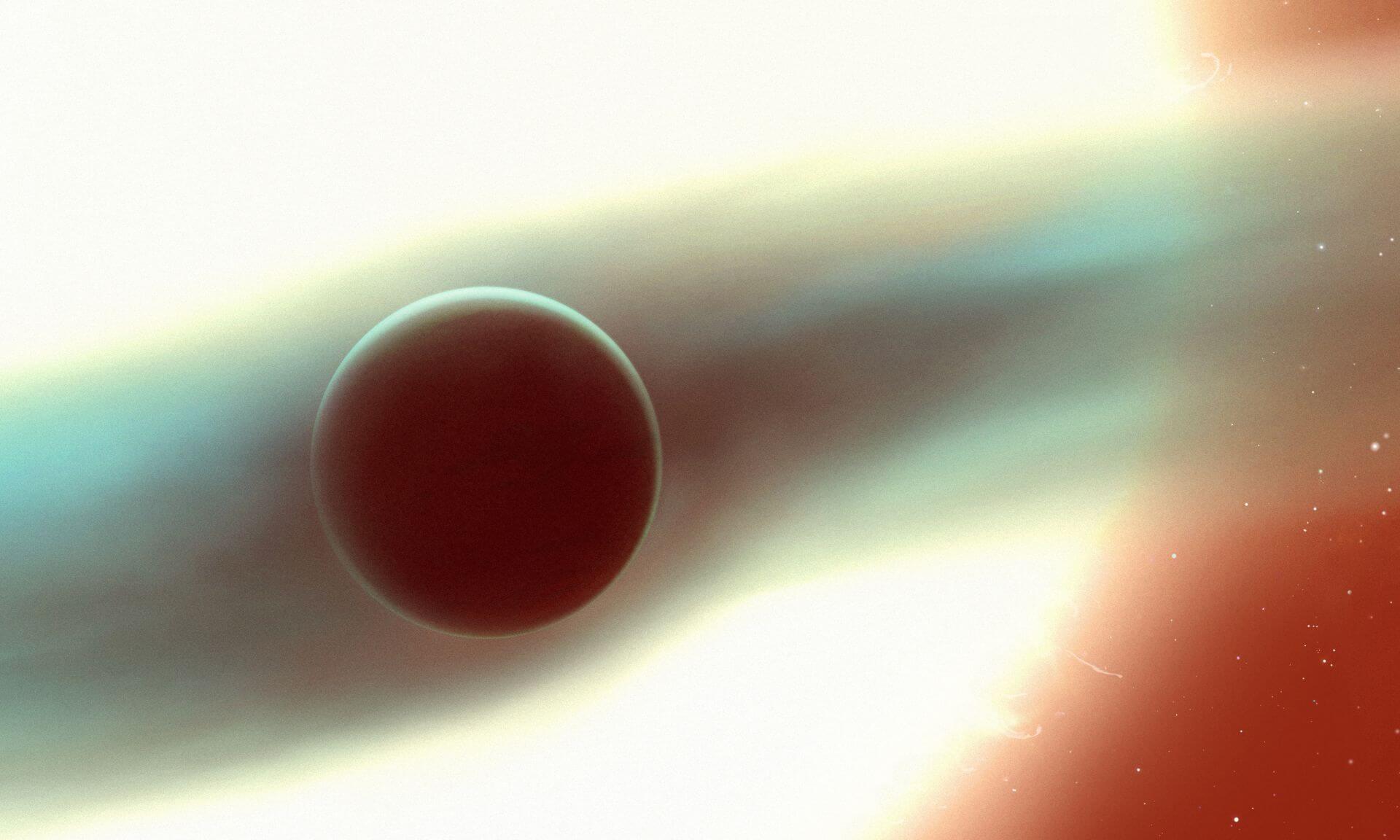

Current computer models of atmospheric escape, such as the one developed at the University of Geneva and adapted for this study, can explain single, comet-like tails, but cannot yet fully explain this newly observed double-structure of WASP-121 b. The discovery suggests that gravitational forces and winds from the star both play crucial roles in shaping these flows, a phenomenon requiring a new generation of 3D simulations to understand the physics at work.

“This is truly a turning point,” said Allart. “We now have to rethink how we simulate atmospheric mass loss — not just as a simple flow, but with a 3D geometry interacting with its star. This is critical to understand how planets evolve and if gas giant planets can turn into bare rocks.”

Beyond the spectacle of the double tails, the finding carries deep implications for planetary evolution. Atmospheric escape, or loss, is one of the key processes that determines whether a world remains a gas giant, shrinks into a Neptune-like planet, or is stripped down to a rocky core. Seeing these dynamics unfold in real time around WASP-121 b gives scientists a unique testing ground for models of how planets change over billions of years. The result may even help explain the ‘Neptune desert’: why the smallest close-in gas giants, known as “hot Neptunes,” appear so rare. They could be the remnants of larger planets whose atmospheres have been eroded by their stars.

Canadian leadership in exoplanet exploration

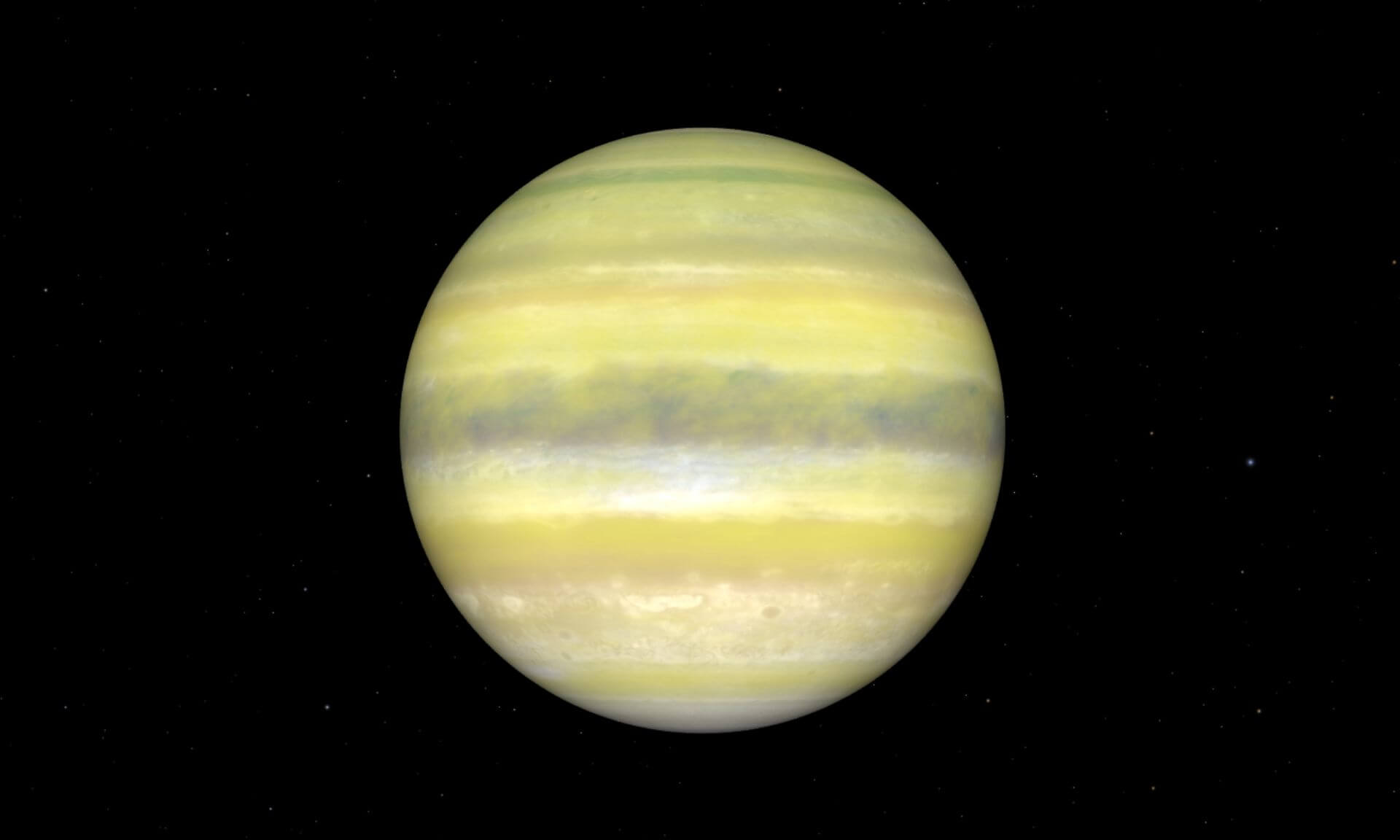

NIRISS is one of the JWST’s four scientific instruments. It was designed and built by the Canadian Space Agency in collaboration with the American multinational Honeywell, UdeM professor René Doyon and the National Research Council of Canada, and it continues to play a central role in many of JWST’s most exciting exoplanet studies. The instrument allows Canadian scientists to probe the atmospheres of distant worlds, revealing their composition, temperature, and now — their escape into space.

“The continuous, high-precision data from NIRISS are what made this discovery possible,” said Louis-Philippe Coulombe, an IREx researcher and the paper’s second author. “The way these observations were performed — a complete phase curve — provides access to many properties of exoplanets, beyond their escaping atmosphere, such as their composition, climate, and energy budget. It’s a clear demonstration of the instrument’s multidisciplinary impact and value to the global exoplanet community.”

In exchange for this important instrumental contribution, Canadian astronomers secured several hundreds of hours of guaranteed observation time on Webb within the first years of its operations. This included the 200-hour NEAT programme, led by David Lafrenière (IREx/UdeM), from which this remarkable data was taken.

Future steps for WASP-121 b and beyond

Helium has become one of the most powerful tracers of atmospheric escape, and JWST’s unique sensitivity now allows astronomers to detect it over immense distances and timescales like never before. While data from ground-based observatories are crucial to help determine the dynamics of a planet’s outflows, continuous monitoring is not possible from such facilities given daylight and weather that break up observations into shorter snapshots.

Future JWST observations will be essential to see whether the double-tail structure found around WASP-121 b is unique or common among hot exoplanets. By studying similar systems, researchers hope to build a broader picture of how radiation and stellar winds sculpt planetary atmospheres across the galaxy to better understand their fate.