What if the energy produced by wind turbines on a beautiful summer day could be stored until January to heat homes in the dead of winter? It might be possible, thanks to the discovery of a new organic molecule that can hold a charge for months with virtually no loss of energy.

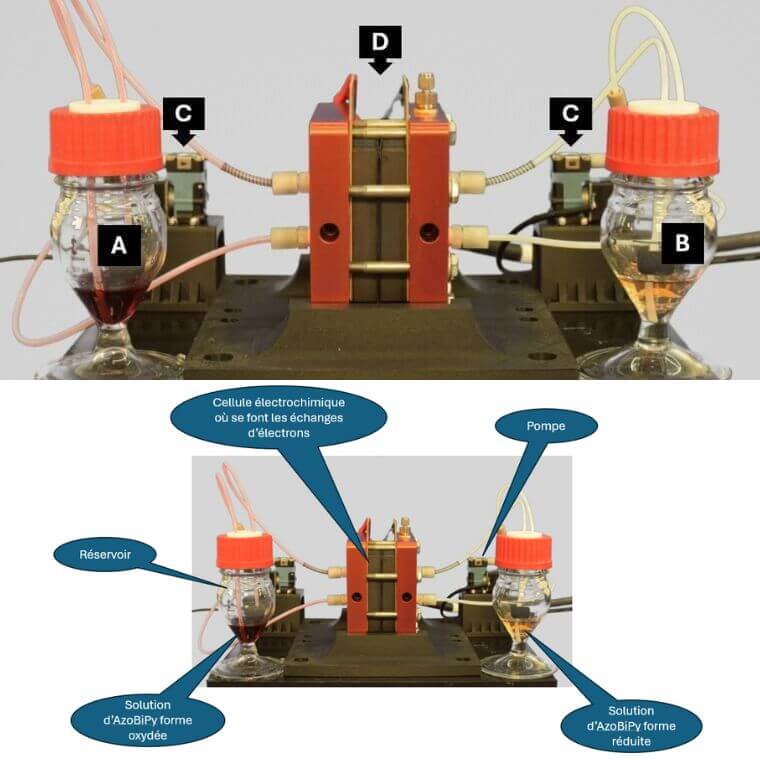

Dubbed AzoBiPy, the molecule was developed by a research team in the Department of Chemistry at Université de Montréal in collaboration with Concordia University researchers. Their results were published last year in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

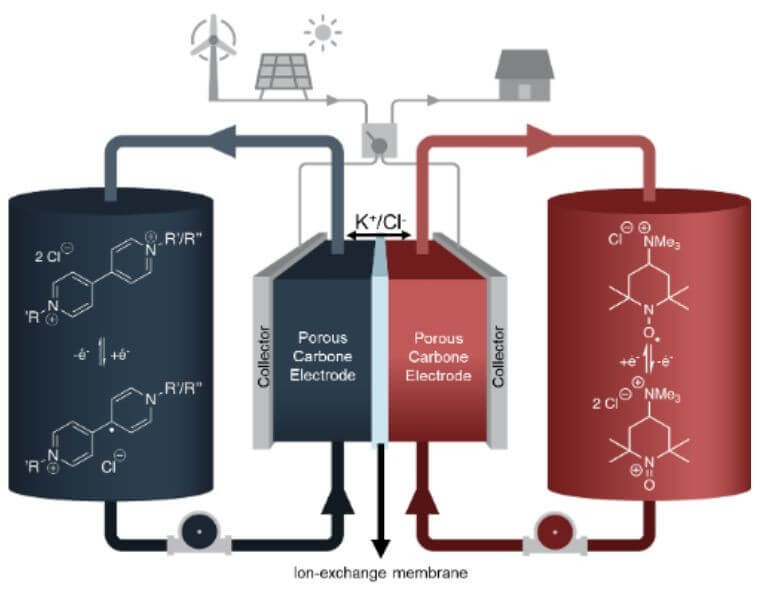

The researchers tested AzoBiPy in a redox flow battery in their lab for 70 days. The molecule proved remarkably stable, losing just 0.02 per cent of its capacity per day. It also stores twice as much energy as most comparable molecules and is highly soluble in water, two critically important properties for maximizing the efficiency of large-scale storage systems.

Led by UdeM professors Hélène Lebel and Dominic Rochefort and Concordia professor Marc-Antoni Goulet, the research team's aim is to find solutions to address the intermittency of solar and wind power, a major obstacle to their full integration into electricity grids.