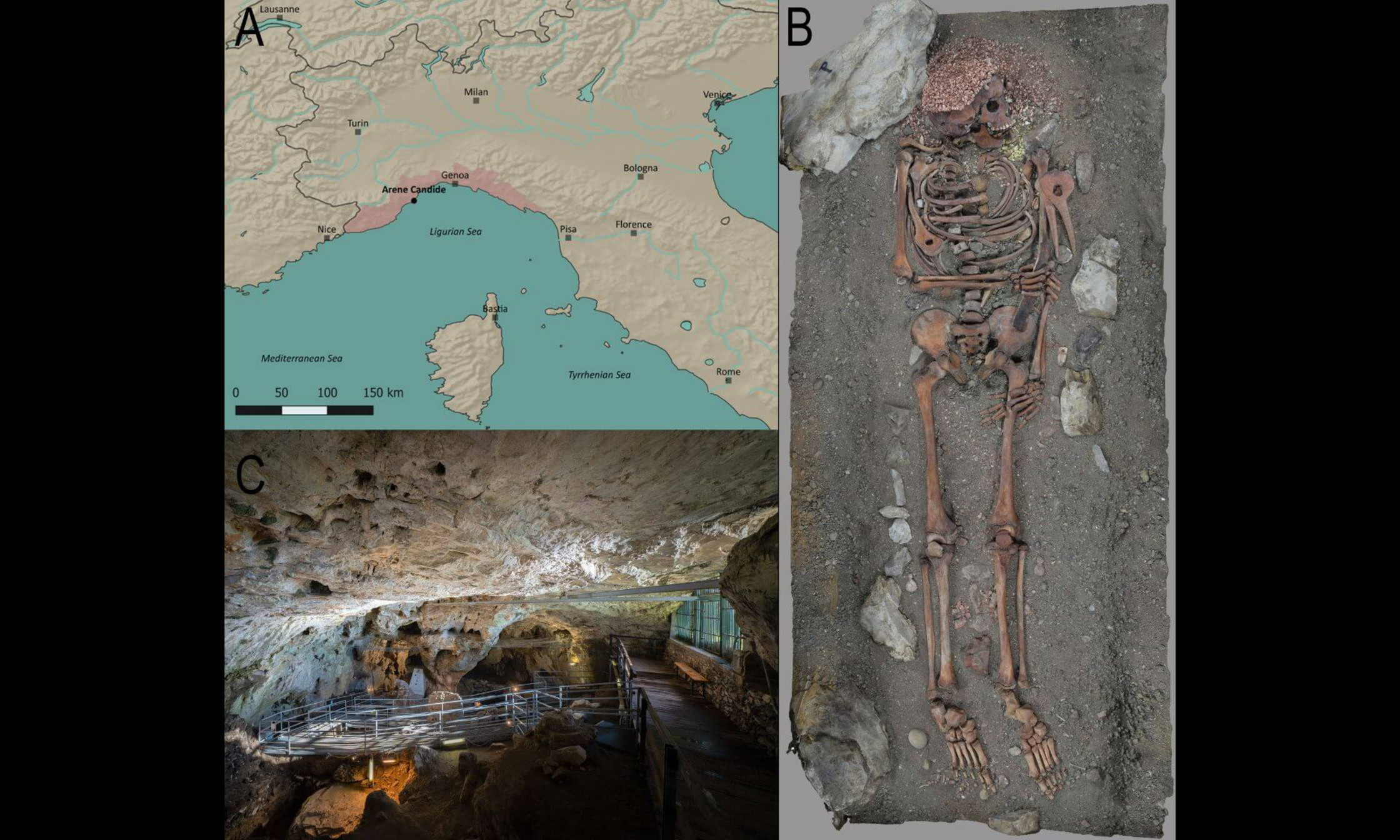

The teenager's skeleton lay supine in a shallow pit on a bed of red ochre, his remains adorned with several ivory pendants, four perforated antler batons, mammoth ivory pendants, and a flint blade, his skull decorated with hundreds of perforated shells and several deer canines.

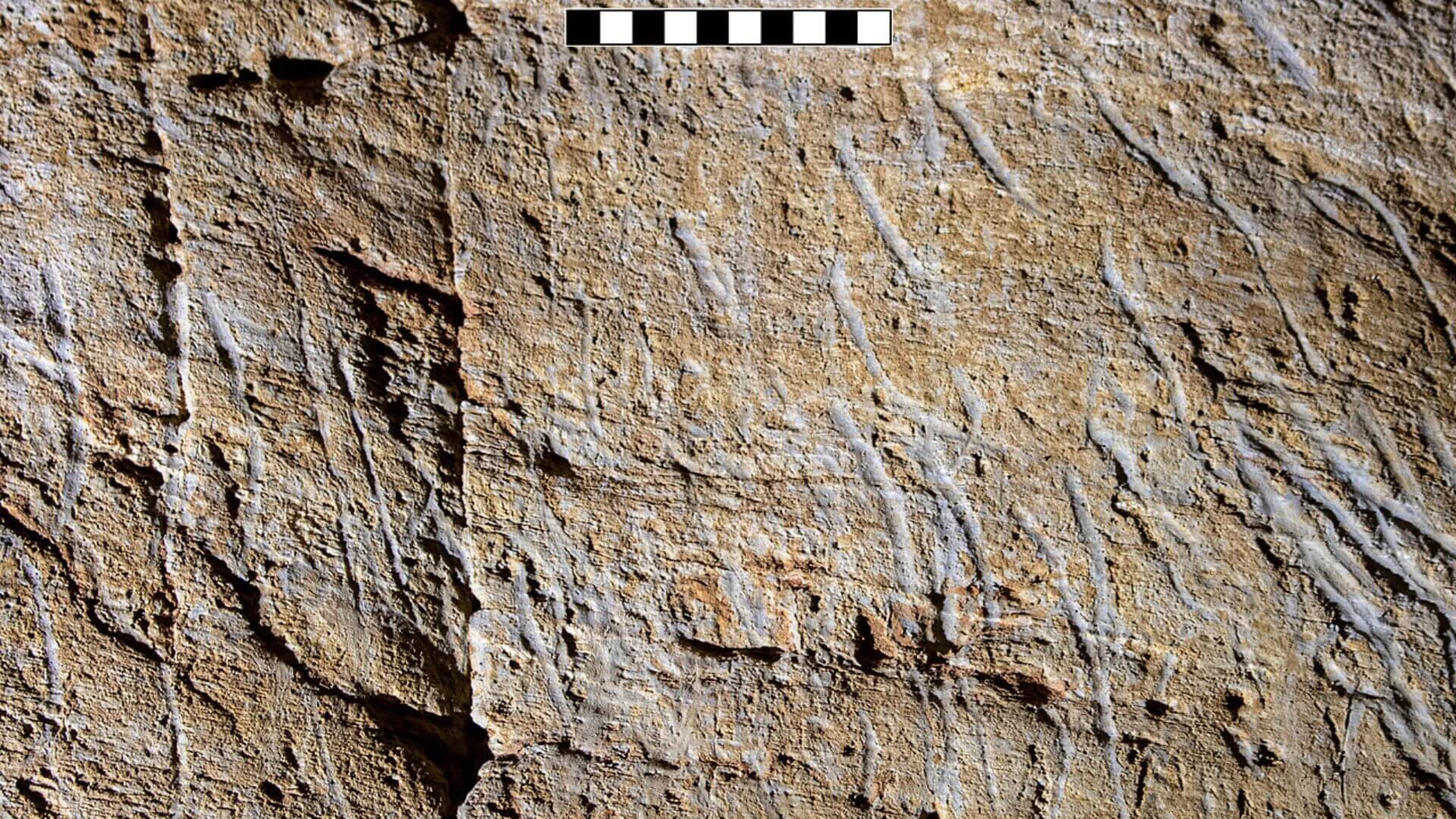

But there was something else that archeologists noticed when they unearthed the ancient remains at the Arene Candide cave in northwestern Italy in 1942: signs of significant trauma to the body at the time of the young man's untimely death.

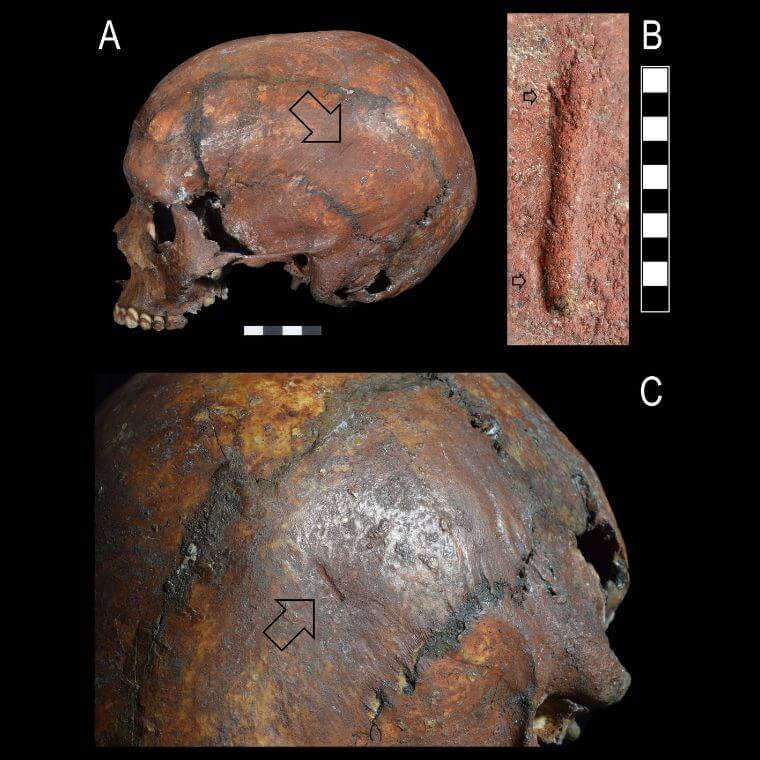

His collarbone, jawbone, one shoulder blade and the top of an upper arm bone were all smashed or otherwise damaged, as were the cervical vertebrae, with those and some missing parts replaced with a large lump of yellow ochre, seemingly to cover his wounds.

There was a clearly defined linear incision on the skull, too.

What had happened? Had the youth been injured in a hunting accident, had he been attacked by a bear or a big cat, or maybe by something else, even a human? Or had he simply fallen from a height? And did he die instantly, or suffer a lot?

No one could say for certain — until now.

In a new study co-authored with Université de Montréal anthropologists Julien Riel-Salvatore and Claudine Gravel-Miguel, an international team of scientists led by University of Cagliari bioanthropologist Vitale Stefano Sparacello painstakingly reconstruct what they think likely killed the teenager some 27,500 years ago.

"This is an exercise in osteobiography that reveals the final moments of a teenager in the Paleolithic era in what is today the region of Liguria," said Riel-Salvatore, a professor and chair of UdeM's anthropology department.

“We can say with great certainty that the youth fell prey to a large carnivore, most likely a bear. He then survived his injuries for some time in agony before dying and being buried lavishly, hence his nickname Il Principe, 'the prince' of Arene Candide Cave.”

It's a significant finding, he added.

"This is one of the very rare cases where we are able to determine the cause of death of a person in the Palaeolithic era."