There are the objects and there are the voices – and now the two have come together as one.

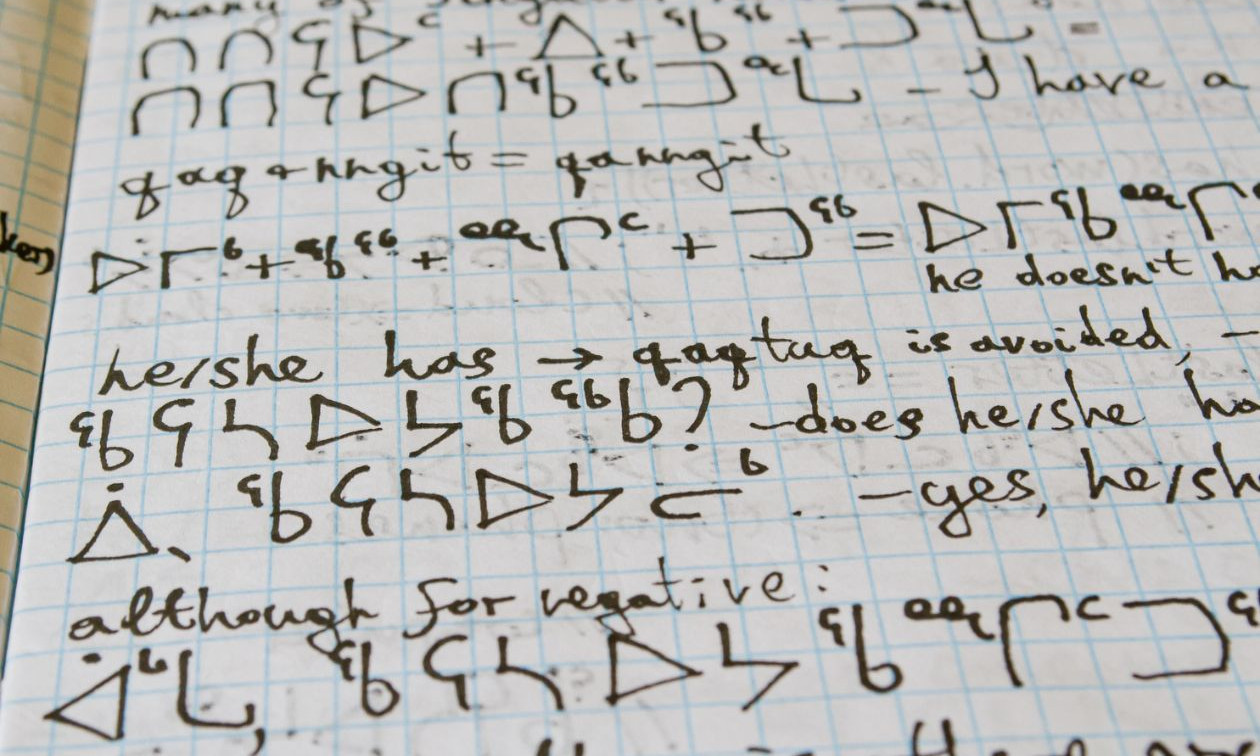

At Université de Montréal, of the 4,000 cultural objects in the Department of Anthropology's ethnographic collection, approximately 500 are Indigenous belongings from the Atikamekw Nehirowisiwok, Innu, and Inuit (Inuinnait, Netsilingmiut, and Nunavimmiut) communities.

In the classroom and online, these objects – everything from snowshoes and baby carriers to knives and oil lamps – can spark learners' interest in history, geography and anthropology, help them understand different societies and territories, and develop an interest in heritage and cultural sensitivity.

But until recently, what was missing from the collection were voices to make them come alive: specifically, the voices of members of First Peoples communities who hold the cultural knowledge needed to interpret the story behind the objects and what they signify.

Now, thanks to an initiative by a specialist in UdeM's Faculty of Education and the members of the team project, those voices can be heard. The project is called Rencontres au coeur de la collection ethnographique, and it's led by Kevin Péloquin, an assistant professor in the faculty's Department of Didactics.