Fear of rejection

The difficulties often arise before a relationship starts, Lecomte said. Her studies show that many people with mental health conditions struggle with low self-esteem, lack of self-confidence and, above all, a deep-seated fear of rejection because of their diagnosis.

The stigma can be hard to shake. Many fear being seen as dangerous, incompetent, unstable or incapable of independence—fears fueled by sensationalist depictions in fiction and the media, but rarely grounded in reality.

The timing of onset can be an important factor. “In men, some psychotic disorders first appear in adolescence or early adulthood—a key period for developing social and romantic skills,” Lecomte said.

Hospitalizations, social withdrawal and missed opportunities can interfere with the process of learning how to flirt, communicate intimately and navigate relationships, she said.

On the other hand, women often find partners more easily. “But that doesn’t necessarily mean healthy relationships,” Lecomte said. “Vulnerability can sometimes attract controlling or toxic people, which creates its own problems.”

Once in a relationship, the obstacles take on new forms. The stigma lingers: partners may fear unpredictability, question their parenting abilities or worry about loss of autonomy.

There are also challenges that stem directly from the disorder itself, particularly in terms of social cognition. This refers to the ability to understand the other person’s intentions, interpret social cues and recognize emotions, in oneself and others.

In some cases, body image issues or sexual difficulties—often related to medication—can heighten anxiety and fears about meeting expectations.

A basic need

Loving and being loved is a basic need, said Lecomte, not a privilege for the few.

“Society long denied this right to people with mental disorders, even excluding them from parenthood, relationships and social life in general,” she observed.

The current reality tells a different story. Today, nearly 70 per cent of people with serious mental disorders lead independent, fulfilling lives. “Some work, raise children, teach or do research, sometimes without anyone knowing they have a psychiatric diagnosis,” Lecomte said.

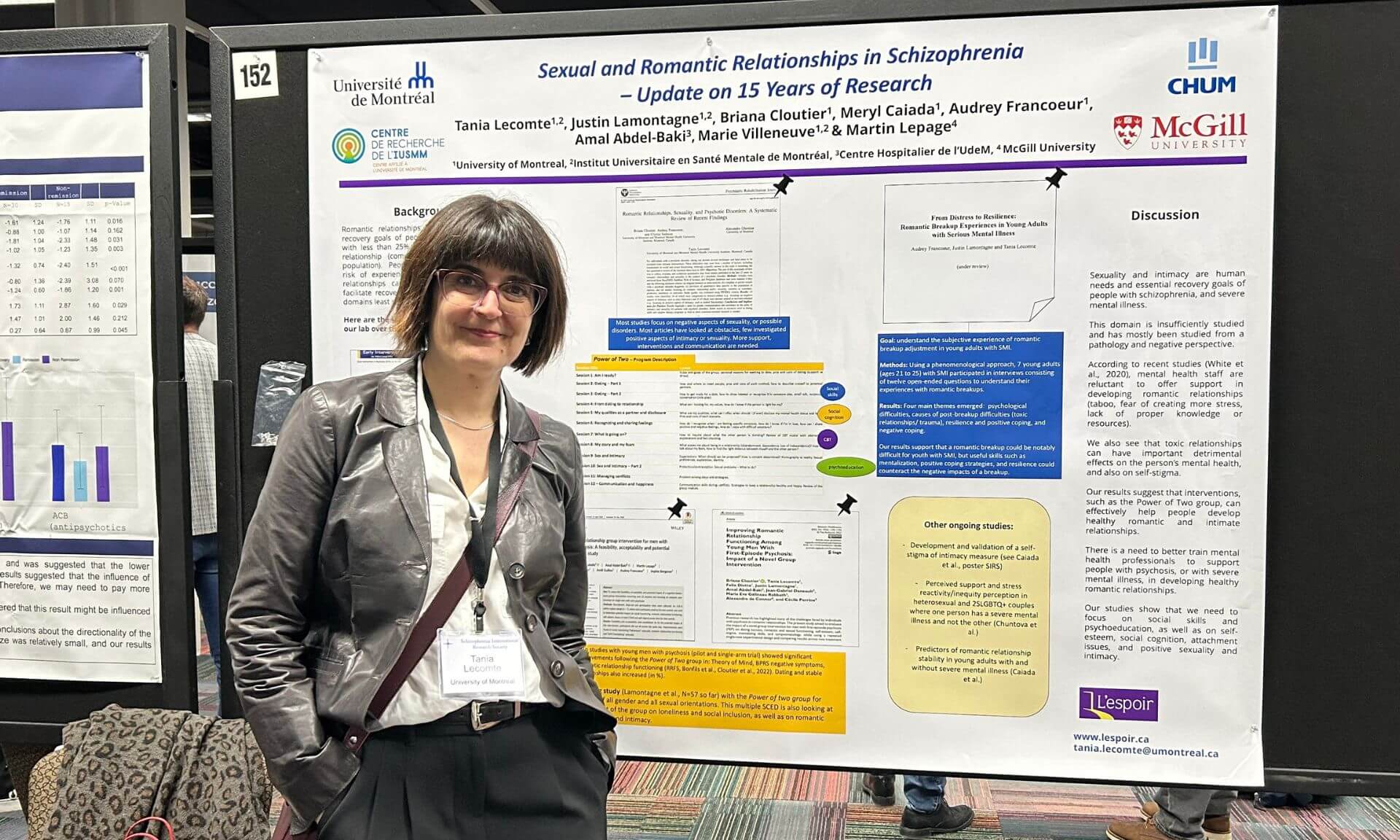

To help people with mental health conditions form relationships, Lecomte has developed a group intervention called “À deux, c’est mieux” (two is better than one). Over 12 sessions, participants work on their personal obstacles, values, relationship expectations, communication skills, conflict management, disclosing mental illness, and the effects of medication on sexuality.

According to Lecomte, the results speak for themselves: participants gain confidence, expand their social opportunities, develop their empathy and improve their ability to put themselves in the other person’s shoes. These changes can be accompanied by a general reduction in symptoms and a stronger sense of connection.

Changing perceptions

Lecomte believes that stigma rooted in misunderstanding is still a major barrier to love.

“Diagnostic labels are problematic,” she noted. “When people think of psychosis, they picture someone living in an altered reality, talking to themselves and rocking back and forth—like in the movies. But people aren’t unwell all the time; these are episodes. Some people experience one episode in their lifetime.”

In short, every individual is different; the same diagnosis doesn’t mean two people will have the same trajectory and identical strengths and challenges.

“If you ask people, ‘Would you date someone with schizophrenia?’ the answer is usually no,” said Lecomte. “But if I introduced you to someone without mentioning their diagnosis, and you spent time with them, you might find them super nice and charming.”

The message, backed by growing scientific evidence, is clear, she said: with the right support and a more nuanced perspective on people's sanity, love is within the reach of all.