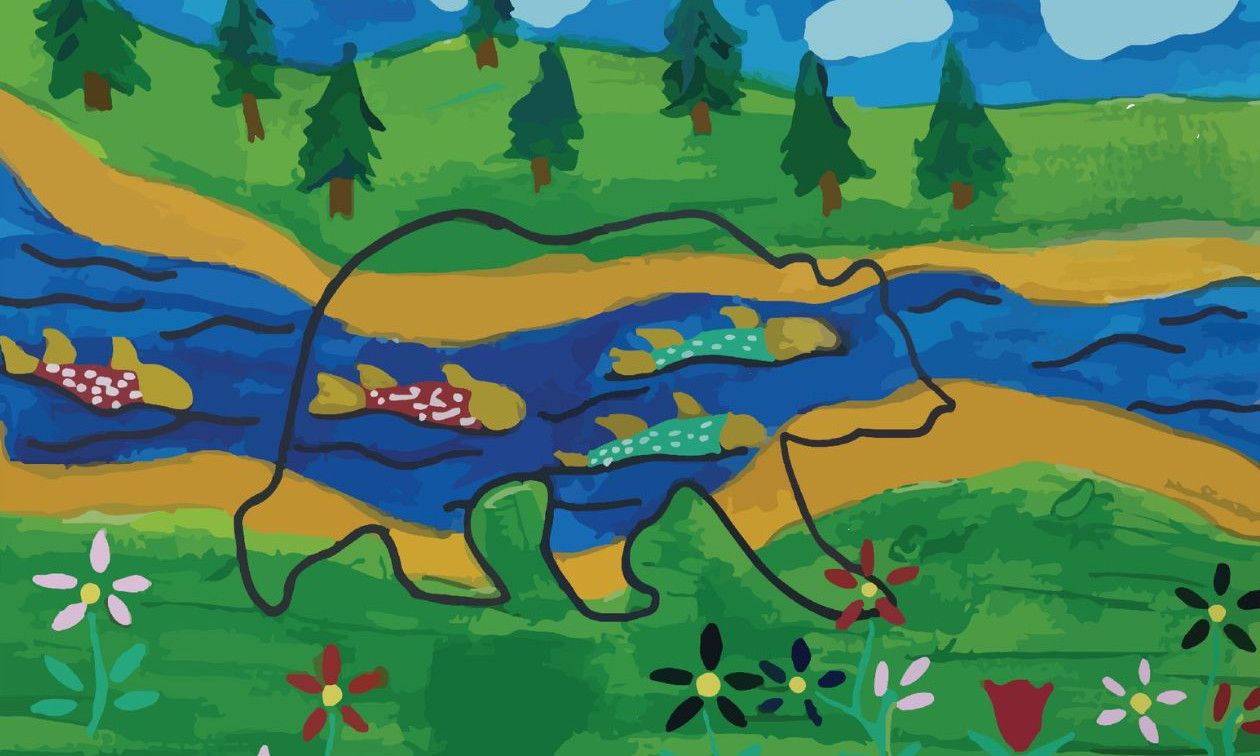

In the Anishinabe language, pawatik means “rapids,” the stretch of river where the current rushes and the water foams and swirls, before ebbing and flowing calm again. The Anishinabeg of Lac-Simon in Quebec’s Abitibi region chose this image for the title of a new history of their nation, for it encapsulates their past.

Their story has travelled over the calm waters of a traditional nomadic way of life, been thrown into turmoil by the whirlpool of colonization, and now opens onto a future in which the waters may run clear again.

The book Pawatik : Les Anicinabek de Lac-Simon racontent leur histoire is the result of several years of work by Miaji, a research group that includes members of the Anishinabe community as well as non-Indigenous anthropologists.

To produce this history, they collected memories from community members, scoured local archives and searched through photo albums. This collaborative university research project was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.